Living with Stone

Stone carries layers of time spanning tens of millions of years, formed through volcanic activity and tectonic shifts. Its density, color, and texture vary by region, giving each stone a unique character shaped by nature.

In architecture, stone has been used broadly — from foundations and structural elements to decorative features — and in recent years, it has gained attention as a local material with minimal environmental impact. Handling stone is, in essence, learning to work with the forces of nature and coexist with them.

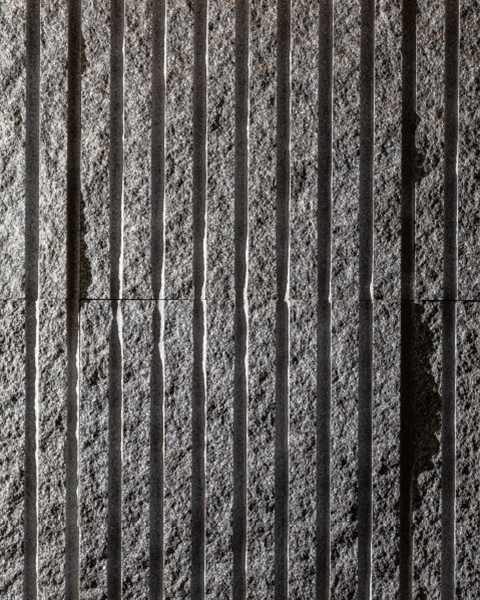

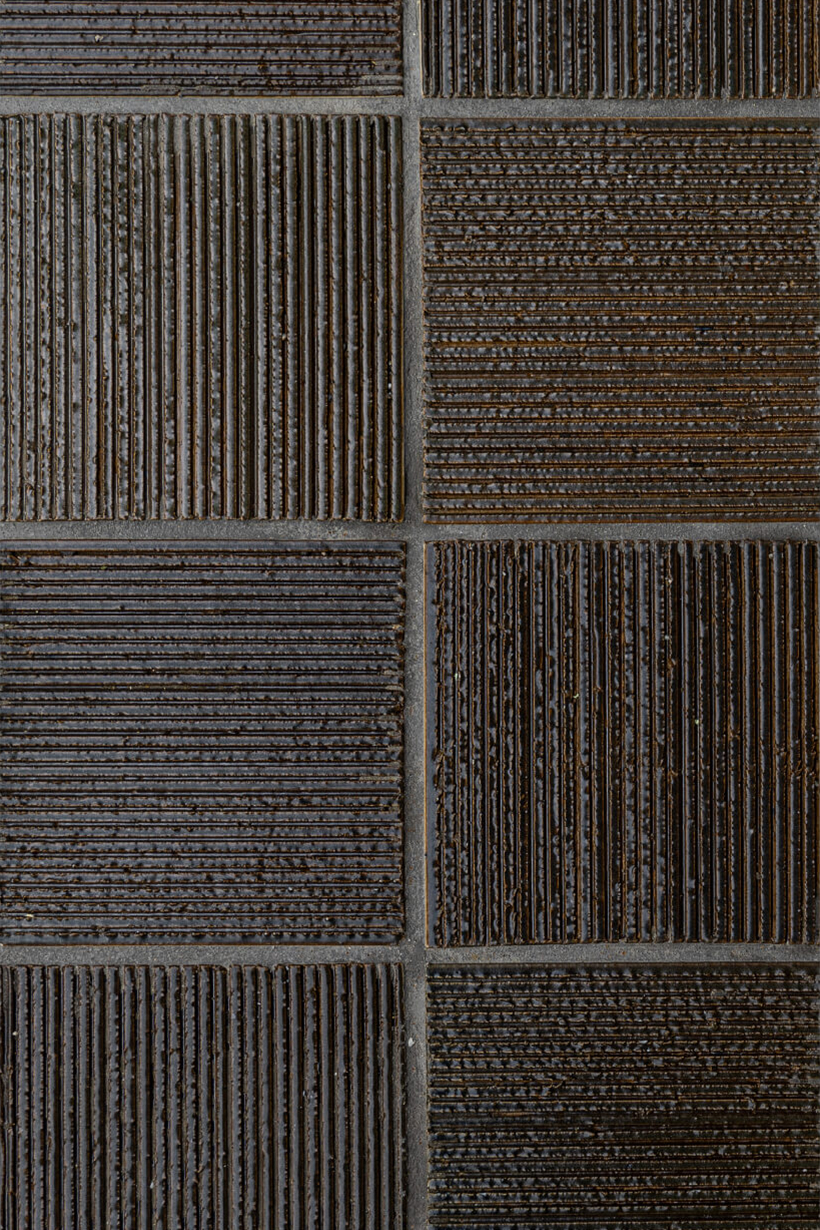

The beautiful bluish Ōshima Stone is one of Japan’s most highly regarded stones. With fine grains and a uniform texture, it excels in durability and wear resistance, making it widely used in architecture and monuments. Its polished surfaces retain their lustrous appearance over time, radiating a quiet presence.When cut, polished, and assembled by human hands, stone begins to mark a new passage of time. It is not merely a hard material, but a presence that quietly tells the memory of the earth.